I travel with film. Not just as some hipster hobbyist—but as a working photographer. I shoot for clients, for community projects, and for myself. I document life. So yeah, I care what’s on those rolls.

I’ve always been careful. I keep film in my carry-on, I ask for hand checks, and I even quote TSA policy when I need to. But in February of 2025, flying out of Mexico City International Airport (MEX), all of that didn’t matter.

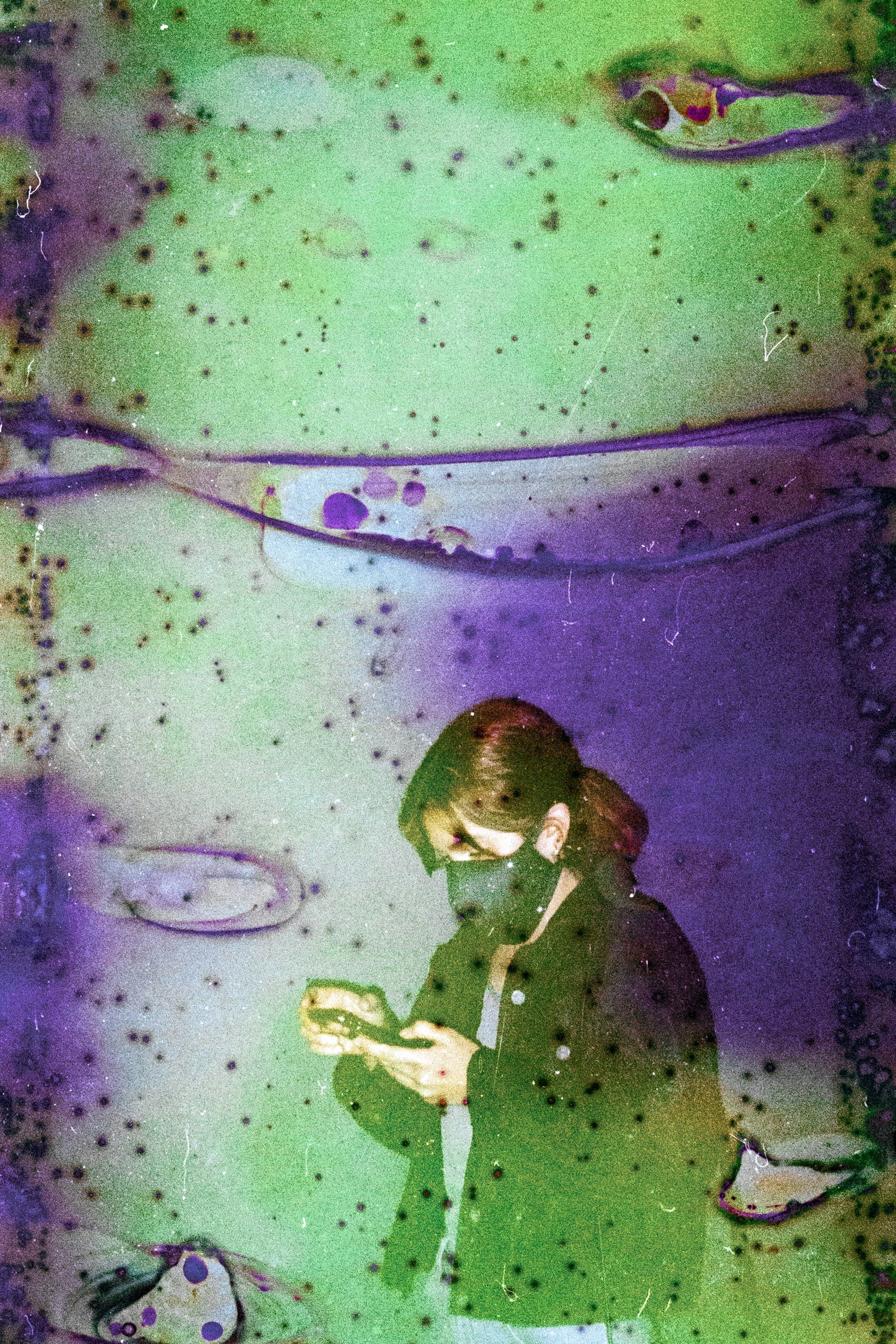

Despite my requests, my film was X-rayed…

What Happened at MEX

I was flying from Mexico City to Atlanta (ATL), then home to Charleston (CHS) with two 35mm cameras and one loaded with 110 film, plus some loose rolls.

At the security checkpoint, I requested a hand inspection—just like I have at airports all over the world. An airport employee tried to help, but his supervisor shut it down quickly.

The loose rolls were hand-checked. But the three cameras, loaded with unprocessed film? They forced them through the X-ray machine.

And while this was happening, I was literally thinking: *Has no one ever flown through Mexico with film before? I’m the first one? I’ve traveled with film in the EU, and I know what to expect there. But here? Why? *

Because I don’t speak Spanish, I had difficulty conveying my concerns. I tried. I really did. But I could tell I was being tossed around, being asked to comply. I stood my ground—until I found myself surrounded by several airport staff members.

At that point, I had to make a call: risk getting into trouble, or cut my losses. I chose not to escalate it further as the intimidation factor made me uncomfortable. I let the cameras go through the scanner. And that sucked.

I’ll be real: I blame the agents at the airport, not necessarily Delta. It wasn’t that I was making a scene—I was calm, but firm. One of the staff members was actually trying to help. He made an effort to translate and kept saying it was a misunderstanding, which to some degree it was—but I also understood exactly what was happening: they weren’t willing to do what I was asking, which was to hand-check the film.

I appreciated his effort. He was kind, and he kept apologizing for not being able to keep up with me; that’s totally understandable. Still, the reality remained: despite his help, the decision had already been made. They weren’t going to accommodate me. And the rest of the staff? It felt like they were more focused on moving me along than hearing me out. Whether it was miscommunication or policy confusion, the result was the same: I was denied a basic, reasonable request that should’ve been honored.

What Happens When Film Goes Through an X-ray Scanner?

If you’re not familiar: once undeveloped film is exposed to X-ray scanning, it’s permanently damaged. You can’t recover the images. You can’t "repair" the film. The damage is chemical—you may not see it until after developing, but it's baked into the emulsion, the intensity varying by film type and intensity of x-ray.

In my case, I lost two rolls of 35mm film, one roll of 110 film, and development costs from Darkroom Lab.

I was told at the airport that Delta would reimburse me for the damage. But I’m reluctant that they will. Their customer service later asked for a "repair" receipt, which doesn't exist for ruined film, but I guess that takes care of development costs.

Traveling with Film: What the Experts Say

According to The Darkroom, a leading film lab and authority on film safety:

“Undeveloped film is sensitive to X-ray radiation. Even though carry-on X-ray machines are less intense than checked luggage scanners, repeated exposures or high-speed films (ISO 800 and up) can be visibly affected.”

But it’s not just about multiple exposures anymore. The real threat now is CT scanners, which are rolling out at airports worldwide.

“New TSA CT scanners emit a much higher radiation dose and can fog or destroy film in just one pass.”

Airport Scanner Types: 2025 Snapshot

| Region | Airport or Area | Scanner Type |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Atlanta (ATL) | CT |

| United States | Baltimore / Washington (BWI) | CT |

| United States | Chicago O’Hare (ORD) | CT |

| United States | Los Angeles (LAX) | CT |

| United States | Most regional / smaller airports | X-ray |

| Europe | Milan Malpensa (MXP) — Terminal 1 | Mixed / CT & X-ray |

| Europe | Rome Fiumicino (FCO) | Mixed / CT & X-ray |

| Latin America | Most major & regional airports | X-ray |

Note: Scanner deployment evolves—always verify with your departure airport.

In the U.S., the TSA recommends that all film (especially ISO 800 and above) be hand-inspected. This includes film in cameras, rolls, and even single-use cameras. Their official guidance is here:

“We recommend that you put undeveloped film and cameras containing undeveloped film in your carry-on bags or take undeveloped film with you to the checkpoint and ask for a hand inspection -The final decision rests with the TSA officer on whether an item is allowed through the checkpoint.“

…eyeroll…

Mexico City Airport's Policy (or Lack Thereof)

According to AICM's published security guide, film is considered a sensitive material and may be inspected manually or by explosive detectors. But as I experienced firsthand, that policy isn’t consistently honored. Many travelers report the same issue: denial of hand checks and X-ray exposure against their consent. Bullshittery.

How to Protect Your Film When Traveling

One tool I recommend (and personally use) is a lead-lined film shield bag. It’s a thick, black envelope-style pouch designed to absorb radiation and help prevent film fog if your bag is scanned. While it won’t make your film invisible to scanners, it does offer an extra layer of protection.

Popular options:

Sima Film Shield Lead Laminated Pouch – Holds up to 22 rolls

The Domke 711-12B Medium Filmguard Bag – Holds up to 15

Kodak Vintage Metal Film Storage Box – Fits 35mm and 120 film. No scanning protection, but compatible with Domke bags (set of 6 colors).

⚠️ Heads up: Some security teams may flag these bags as opaque and pull you aside for a manual check. That’s actually ideal—because that’s what you want anyway.

Film Travel Tips: How to Protect Your Work

If you're flying with film, here’s how to avoid what happened to me:

✅ Always carry film in your carry-on bag

✅ Use a clear plastic bag for fast inspection

✅ Request a hand check clearly and early (check out this sticker template for 4x5 film)

✅ Print the airport film policy for other visiting countries and keep it ready to share.

✅ Avoid CT scanners when possible

✅ Ship your film home undeveloped via courier if unsure

Final Thoughts

I didn’t write this for sympathy. I wrote this because I don’t want another photographer—or anyone shooting analog—to lose work over something avoidable. I did everything right. And I still lost my images.

Am I pushing Delta for a refund? Meh, it’s around $75. The sentimental value is more. What I really want is a policy change.

I want airlines and airport security to recognize that film photography is alive and real. That our work matters. That the solution—hand checks—already exists.

If you’ve had film ruined while traveling, share your story. The more noise we make, the harder it is to ignore.

Let’s protect the medium—and each other.

-V

UPDATE: Since publishing this post, I received responses from both PROFECO (Mexico’s consumer protection agency) and Delta Air Lines. Here's the update:

PROFECO confirmed they do not have jurisdiction over customs or airport security staff. They referred me to the Mexico City Airport complaint form and stated that damage claims must go through the judicial system with legal representation in Mexico. Not exactly helpful—but at least it clarified the limits of their authority.

Delta Air Lines acknowledged my complaint and opened a case. After some back and forth, Delta reimbursed me $66.95 for film development costs via ACH transfer. It’s appreciated—but this was never just about the money. It was about the principle, the miscommunication, and the effort it took to get a basic issue acknowledged.

I’m frustrated, but not surprised. It’s a reminder that relying on policy alone doesn’t always protect you, and that we often have to advocate harder than we should just to be taken seriously. There’s no clear accountability when this kind of thing happens, and that’s why I wrote this post in the first place.